Giorgio Samorini is one of the great scholars, perhaps the last, in the ethnobotanical study of the use of intoxicating plants in living and extinct cultures. Samorini, originally from Bologna (Italy) but residing for years in Mallorca, will attend Fuertedélica 2024 to talk about “The Cults of Iboga,” a fascinating topic on the use of this entheogenic plant in Gabon and other West African countries, a subject Samorini has been studying for thirty years. Here is a small preview of his talk.

When did your interest in iboga begin?

In 1991, I traveled to Gabon for the first time. I didn’t know anyone there, so I searched for several days until I found the first Bwiti temple in Libreville, the capital. There began my relationship with Bwiti, which many associate with a religious cult, but it is actually a more complex matter that includes initiation rites, divination, prophecy, possession, and religion. Therefore, I prefer to speak of “the cults of iboga” rather than just Bwiti.

How many branches are there in the Bwiti religion?

Bwiti is divided into hundreds of different sects, but there are basically two main branches: one that does not accept Christian symbols and another, the Bwiti of the Fang, which is syncretic and uses a lot of Christian symbolism and rituals. These two groups do not accept each other, but the Fang have gained strength in Gabon thanks to the inclusion of these Christian symbols, competing with Christianity and Islam. The Bwiti of the Fang is considered the third religion in Gabon.

Tabla de Contenido

ToggleInitiation to Bwiti

Do you continue to research these cults?

The last time I was in Gabon was Christmas 2022, so I have been studying the cults of iboga for over thirty years. I conduct field studies and also study literature, which is mostly Francophone because the French are the ones most interested in this topic. The Sorbonne University in Paris is the nucleus of these studies, which is why most of the literature on the cults of iboga is in French. For this reason, I am publishing a series of articles in English about iboga, which will include eight or ten articles in anthropology journals to further internationalize Bwiti.

How did you get authorization from the religious authorities in Gabon to study Bwiti?

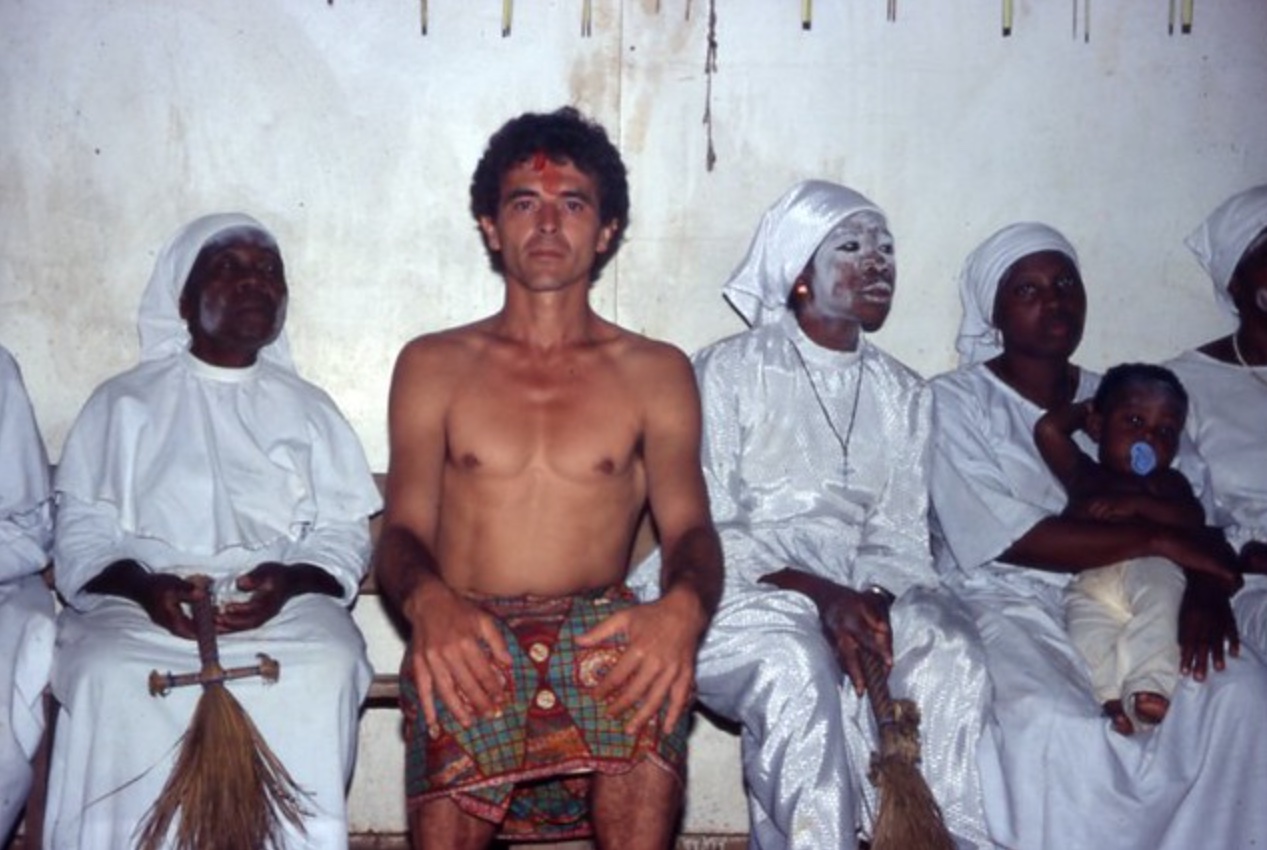

I was initiated into Bwiti by a Fang community in 1993 because I wanted to study the initiation rite well, one of the most dramatic I have known. They made a condition: “if you want to study us, you must undergo initiation and then you can study.” It is a risky rite where you put your life in their hands. After undergoing it, I understood why no white people have been initiated into the Akanga sect. This initiation has opened doors for me to several Bwiti groups, as by pronouncing the “magic” words, I have been allowed to access their ceremonies.

What difficulties did you encounter in this research because of your European status?

It was a very difficult study because Gabon is a complicated primary jungle. I couldn’t reach all the places I wanted due to logistical difficulties. I couldn’t stay in the primary jungle for more than 20-22 days, as it is estimated that after this time, the possibility of contracting a tropical disease becomes exponential. Therefore, I always stayed around 20 days and returned to the capital. How many missionaries, how many researchers have died in that jungle?

You can die from malaria or from iboga itself. There seem to be many ways to die in Gabon.

Yes, many have died from iboga. Whenever I returned to Italy, I went to the tropical diseases center for a check-up because it is truly dangerous. Gabon has Ebola, elephantiasis, the tsetse fly, among other diseases. It is somewhat like New Guinea, which is considered a cursed area by ethnographers.

Keynote Lecture

What will you tell us at Fuertedélica on November 22?

I will talk about the rites of iboga, a little-known topic beyond Bwiti. There are therapeutic and possession rites, different from the religious cult. In possession rites, when taking iboga, a spirit enters your body, acts, and speaks through it, teaching you about your problems. There are also divinatory rites to solve material or personal problems. There are differences between the male and female use of iboga; possession rites are carried out by women, while religious rites are performed by men.

It is curious how cults like Bwiti or Santo Daime reclaim the entheogenic sacrament used by early Christianity, which it abandoned to commune with this “insipid host,” as you define it.

Yes, Bwiti followers say, “We are the true Christians,” and criticize Christians who use the host “without knowing what they are talking about.” They are very critical and almost fanatical in their Christianity… but with iboga. The center of revelation, of direct contact with the divinity, is iboga, so they have a well-founded criticism against Catholics. There is an ideological conflict with Catholicism in Gabon, although not as violent as in the 1930s when there were military confrontations and Bwiti martyrs.

Are you referring to a religious war with iboga involved?

In the 1930s, a physical war also began through colonial military forces. Many Bwiti followers were killed, they have their martyrs, and some were even killed by priests. Today, there is still a conflict in which Bwiti followers seek recognition as the third official religion of the state. Politicians see them as an important electoral mass, but in the end, Catholics interfere with their recognition. However, we are not at the level of the persecutions of the 1930s.

Entheogenic Religious Wars and Iboga

And it is a religion that I understand is also breaking borders. It is expanding, right?

Yes, in West Africa, Bwiti has been present for some time in five countries besides Gabon: Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Cameroon, and now it is reaching Angola and Nigeria, so it is spreading in areas where iboga is present. We must differentiate between wild iboga and cultivated iboga from various subtypes of Tabernanthe iboga. It should be noted that in none of these nations is it illegal.

What are the ecological implications of this expansion? We understand that it is already being overexploited and that the pharmaceutical industry is also pressuring for the known therapeutic effects of iboga.

Yes, there is an ecological problem, but the cause is not the expansion of Bwiti in these African nations, but the demand for material from Europe. Pharmaceutical companies and the spread of iboga in Europe lead to more exploitation than cultivation. The root of iboga must be at least seven years old to be effective, and many cultivators do not wait, resulting in low-quality iboga in Europe. Iboga is extremely potent, one of the greatest hallucinogenic plants we have in the world, and just a teaspoon is enough to feel its potency. The problem is not the religion but the Western culture that wants to exploit it for pharmaceutical or recreational purposes. When I go to Gabon, I don’t see a shortage of iboga. The problem only occurs in areas where it is cultivated for sale to Europeans, such as Angola or Cameroon.

The ICEERS scientific team, led by Dr. José Carlos Bouso, has just completed a study on the use of ibogaine for methadone withdrawal, using Voacanga africana instead of Tabernanthe iboga precisely due to overexploitation.

Yes, ibogaine is present in other African plants, but the cults of iboga revolve only around Tabernanthe iboga.

Giorgio Samorini will give the keynote lecture “The Cults of Iboga” on November 22 at Fuertedélica.

Get your discounted ticket at this link.